“This article was originally published in www.soydanbay.com and shared with the author’s consent.”

Over the last two decades, brands have become 200% less distinct from one another. The ones that stand out, however, have something in common: they integrate two seemingly opposing personality traits. In this series of blogs, I offer different methods to discovering and leveraging the duality embedded inside your brand. By tapping into these insights, you could make your brand stand out.

Motivational and archetypal duality

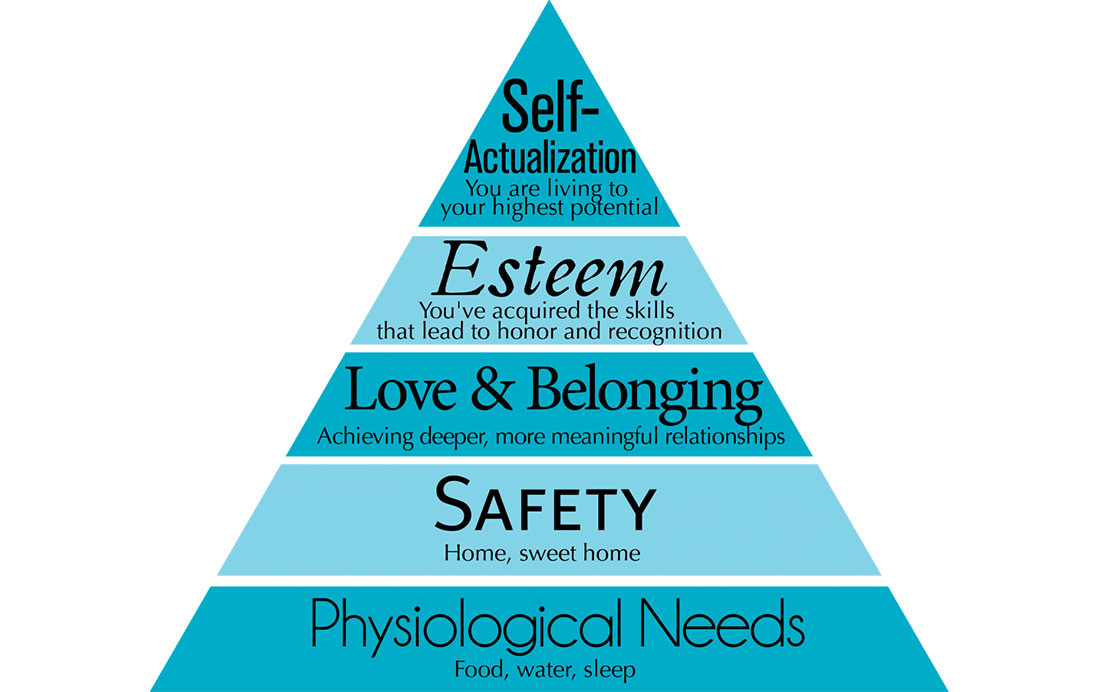

Back in 1943, Abraham Maslow wrote an important scientific paper titled “A Theory of Human Motivation,” explaining the hierarchy of needs. His theory was that the physiological needs are fundamental and have to be fulfilled to survive. Then came the safety needs, which ranged from physical safety to financial security. Next followed emotional needs such as love and belonging. Towards the top of the so-called pyramid situated the esteem, which included the lower esteem needs (outward oriented) such as to be respected, recognized, and higher esteem needs (inward oriented) such as self-respect, confidence, mastery, independence.

At the very peak, self-actualization stood alone, representing the fulfillment of one’s potential, accomplishing everything one sets out to do. Before he died, Maslow revised the highest need from self-actualization to self-transcendence, believing that the self only finds its actualization in giving itself to some larger goal outside oneself, in altruism and spirituality.

It turns out that Maslow got many things right, but one fundamental thing terribly wrong. While the existence of universal human needs was true, there was no sign of a hierarchy. (In fairness, some claim it wasn’t Maslow but his followers that drew the pyramid, though Maslow thought that some sort of hierarchy did exist.) The pyramid metaphor was just an illusion or yearning for order and control. Today, modern science agrees with what Aristotle once said: Man is by nature a social animal. We are biologically hard-wired for collaboration, without which there is no survival. Also, people often risk their physical safety as well as financial security for their loved ones. Likewise, consumed by the Flow state of mind, people could easily ignore their physiological needs for hours.

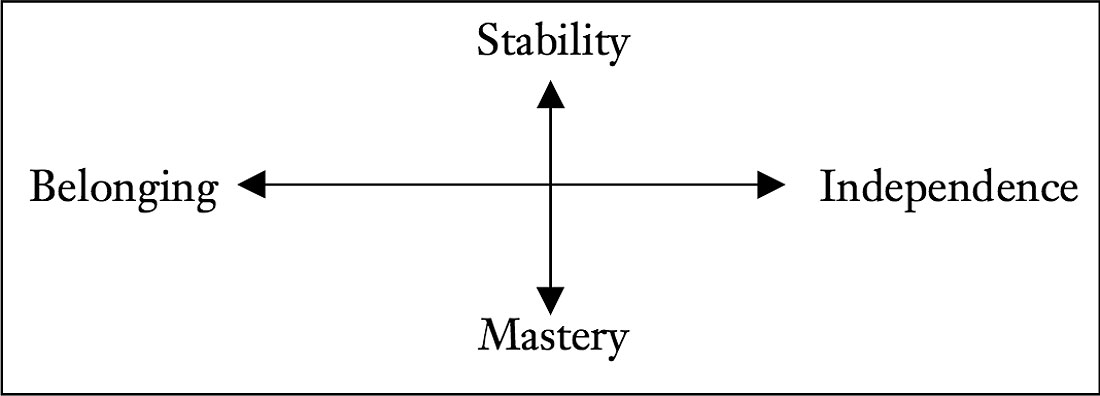

Long story short, human needs are universal, but there is no hierarchy among them. Life is a complex web requiring constant negotiations. That’s why a better approach is to visualize those needs as opposing poles instead of layers of a pyramid. Independence pulls us in one direction while belonging tugs us off in other. Stability attracts us away from mastery, whereas mastery drags us away from stability. As you can see, tension is already embedded in universal human needs. We just need a roboust framework to harness this energy. For that, let’s polish our knowledge of psychology.

When we hear the word unconscious, we tend to zero in on the personal unconscious. Championed by the legendary psychiatrist Sigmund Freud, this discipline focuses on the personal experiences that have been forgotten or repressed, yet linger in the personal unconscious mind and motivate, shape, or control much of our behaviour.

There also exists, however, a different level of unconscious brought to light by Carl Gustav Jung, another revolutionary psychiatrist. He firmly believed that somehow the collective experiences of the human race are embedded into the minds of all men and women. For instance, every human society that existed, is existing, or will ever exist have the concept of the Hero. It might be portrayed as a Samurai in Japan, a cowboy in the States, or a Maori Warrior in New Zealand. Why does such a universal idea exist? We don’t know. How did it form? We don’t know. Where does it come from? That, we know. And the answer is the collective unconscious.

Universal themes that constantly run in the minds of humankind are called the archetypes. The hero is not the only archetype, to which we can all relate. The sage, the companion, the child, the trickster, and the rebel are some of the character archetypes we can all grasp intuitively. Also, character archetypes aren’t all there is to it. There are situational archetypes such as the journey, the fall, and the initiation as well as symbolic archetypes like light vs. darkness and fire vs. ice. But for the sake of our discussion, let’s focus on character archetypes.

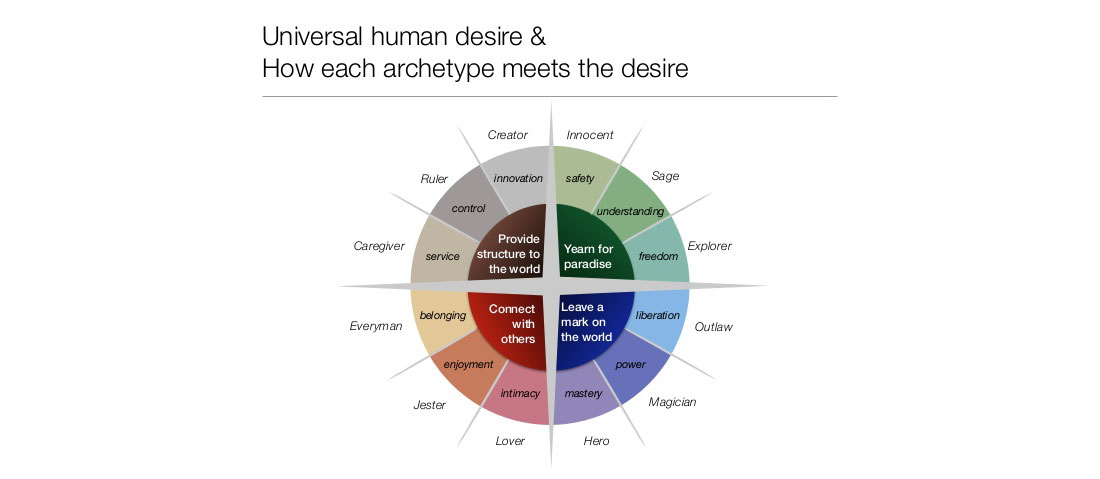

The truth is, probably there are as many archetypes as there are storytellers in the world. Likewise, there are so many ways to categorize them. Arguably the best effort to date, however, comes from Carol Pearson, who in Awakening the Heroes Within described 12 distinct archetypes. Then, in the Hero and the Outlaw, with the help of Margaret Mark, she connected her 12 archetypes with motivational categories. Here is how Pearson&Mark’s system looks.

So, how can you use this system to discover your brand tension? Every category has a dominant archetype. Finding yours, then integrating it with the elements of another archetype from the opposing pole could be an option. Let’s see this method in action.

If the dominant archetype of the category is the Hero, then you can try to blend characteristics of an archetype from the Stability category. Example: Nike is a typical Hero brand. With its Nike+ apps and services, though, it empowers (and helps being acknowledged) users, tapping into the virtues of the Ruler archetype.

Or take shaving for example. In Brand Meaning, Mark Bates says, “Research reveals that men feel reborn when they had just shaved—as if returned to their original pristine state, the way they were when they entered the world.”

In other words -regardless of what Gillette wants you to believe- the archetype of the razor blade category is the Innocent. The Jester archetype lies at the polar opposite of the Innocent. Dollar Shaving Club became a billion-dollar company by just unleashing its inner Jester.

Finally, let’s look at M·A·C. The cosmetics industry is all about beauty, which is the purview of Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty, fertility, and sexual love. Therefore, the archetype of the category of Cosmetics is the Lover. By tapping into the virtues of various archetypes from the opposing pole, M·A·C became a Breakaway Brand. Here is a -mildly edited- excerpt from the brand’s website:

- M·A·C is the world’s leading professional makeup authority because of our unrivaled expertise in makeup ARTISTRY. (the Sage)

- M·A·C celebrates diversity and INDIVIDUALITY – we are for All Ages, All Races, All Sexes. (the Explorer)

- M·A·C is at the forefront of fashion TRENDSETTING, collaborating with leading talents from fashion, art, and popular culture. Our Artists create trends backstage at fashion weeks around the world. (the Explorer)

To sum, this approach has three steps. First, you need to understand the archetypal meaning of your category and deliver on it spectacularly. Second, you must find an archetype -one that is not already being used by your competitors- from the opposing motivational pole. And third, you should integrate the elements of that archetype into your brand promise and personality.

On the fourth instalment of this series, we will dive deeper into the realm of character archetypes and explore an alternative way to generate brand tension.

Connect with Günter Soydanbay on LinkedIn or Twitter or simply email him gunter@imeanit.com